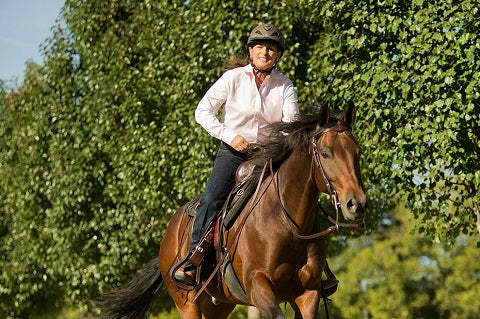

Troxel Athlete and Horse Master Julie Goodnight has more than a quarter-century of horse training experience. Her varied background ranges from dressage and jumping to racing, reining, colt-starting, and wilderness riding. Her training and teaching techniques are frequent features of Horse & Rider, The Trail Rider and America's Horse and she makes frequent appearances at horse expos, conferences and clinics.

Julie Goodnight takes on topics you want to know more about in her online training library—part of her ever-expanding Horse Master Academy and television show, Horse Master TV. Check out her full list of clinics and appearances at: JulieGoodnight.com/calendar. Here, Julie discusses learning to let go and allowing your horse to move forward.

I've learned to recognize the signs of the horse who's afraid of the canter departure. I've seen it many times throughout my career: A "forward" horse (with too much go) works just fine with the rider at the walk and trot, but when cued to canter throws a wall-eyed fit.

To me, an "explosive" canter departure is one where the horse--when cued to canter--throws his head up in an emotional fit, grabs the bit and takes off at a gallop (crow hopping and bucking as he runs increasingly faster). Often the horse will settle into a nice steady canter after 6-8 strides of crow hopping if you ride through the initial drama. That is the hallmark of the horse that is afraid of the cue--it's not cantering that bothers him, it's just the moment of departure.

The Cause

If a horse does this, he has learned to fear the cue and distrusts his rider. Of course you must rule out any kind of physical issue or saddle fit problem--which may be contributing to the problem. After that is ruled out as an issue, an explosive canter departure is often caused by one of two things. Either the rider has grossly over-cued the horse, or the rider has inadvertently hit the horse in the mouth on the very first stride. Often it's a combination of both.

A really forward-moving horse requires very little cueing and probably no leg cues at all. A novice rider learning the canter cue and trying to follow the complicated instructions in an uncoordinated way will almost certainly over-cue a forward horse. Some horses are so easy to get into the gait that cueing them should be more of an “allowing” them to canter than actively cueing for the canter. For those horses, as soon as you start riding it, they canter; as soon as you think canter, they step into it. Many riders have trouble bringing the cue down to the horse’s level of sensitivity; and instead, they over-cue and end up with a canter departure that looks like the horse was shot out of a cannon.

When the horse goes into the canter, he first lifts up and rocks back on his haunches, then lunges forward, pushing off with his hind legs as his nose dives down into the bit. If the rider is afraid to canter, she freezes up--at the moment the horse lifts up to push off into the first stride and clinches the reins. This causes the horse to hit the bit hard as he lunges forward and hurts his mouth. In that moment, the rider has essentially punished the horse for doing what she asked. So you can see how that might make a horse a little emotional and it would make it hard for the horse to trust the rider.

Fearful Horses

Recently, I met a horse and rider who were the poster children for this combination of training problems. It was indeed a very forward horse—one you only need think into the canter. He was a very handsome and kind-looking sport horse and he worked beautifully for his rider at the walk and trot. I knew as I watched her warm up, first with groundwork and then mounted work, that she was afraid to let the horse move forward and she seemed obsessed with control—stopping every-other step. Go-stop-go-stop.

The best thing you can do with a forward horse is let them move forward. A lot. Make them think it’s your idea. After all, forward motion is the basis of all training. Watching her, I knew that she was afraid of the horse’s forward energy and she was obsessed with controlling and containing it rather than just letting the horse move out with some freedom (and trust). I was not surprised when she declined to ask the horse to canter; she was sure he would go ballistic at any moment. That wasn’t the same impression I had of the horse—he seemed kind and willing.

Yes, her horse had a history of bucking at the canter departure. Indeed, it was the very problem that brought him to be a cast member on my Horse Master with Julie Goodnight TV show. All the signs pointed to a horse that was emotional at the canter departure because he had been over cued, then halted with heavy hands as soon as he took off into the requested gait. The rider had no reason to trust the horse, but the horse had even less of a reason to trust the rider. After being asked to move forward, then hit in the mouth by her halting rein cues, he learned that the canter was something to fear. It was going to hurt. With this riding pattern, she constantly reminded her horse not to trust her. Asking him to do something then criticizing him when he did it would understandably cause resentment.

For the rider, her obsession for stopping was about wanting to make sure she had control. Ironically, she would have far more control (and far less emotionality) by letting the horse move forward.

The Answer

When I got on the big, warmblood gelding, my plan was to move him out at a strong trot, changing directions frequently and flexing his neck a lot, to get some of his forward energy in check. He was very responsive and it wasn’t too long before I was the one pushing him forward and he was thinking slower might be nice. When I felt he was ready, I reached way forward with both my hands, sat on his back and then gently started moving my seat in the canter rhythm. His first transition with the new canter cue was a bit exuberant, some might say explosive. He crow hopped and offered a small buck. But in just a few strides, he settled into a lovely working canter in a soft and rounded frame.

At that moment, I knew my initial suspicions were correct. He had been afraid of the transition. He wasn’t unwilling to canter. A soft cue and teaching him that I would not touch him with my rein aids allowed him to gain confidence and start to trust me.

With each subsequent transition from trot to canter, he was smoother and smoother as he came to understand two important things. First, that I would not hit him in the mouth or snatch up the reins when he did what I asked (me reaching extra far forward with my hands as part of the cue was my promise of that). Secondly, I would not “yell” at him (over cue) when I asked for the canter.

Turned out that the Reach-Sit-Pump cue was fine for him—he required no leg aid and hardly any seat aid to canter. Soon, the horse was stepping nicely into the canter with a very relaxed back when I reached and sat (no pumping of the seat required). He quickly gave his trust to me; horses are amazing that way—if you change the way you are doing things, they come right along with you.

Learning to Trust

Getting him to trust his owner, and her to trust him, was a greater challenge. It is a huge dilemma; when you are riding a horse that feels too fast and you have visions in your head of the horse running away with you, it is very hard to give him his freedom and let him move forward. But that is exactly what the horse needed. Time and time again, when horses are going too fast, loosening of the reins is what causes them to slow down. But it takes a lot of willpower, when you are afraid, to trust the horse and give him his freedom.

The horse that is bucking or crow-hopping at the canter needs to move forward at the canter until he relaxes his back and then allow him to stop (stopping a bucking horse only serves to reward his bucking). Nothing could be harder than to let go of a tight hold on a horse that you think you cannot control, but this rider did an incredible job. She was an excellent rider—certainly more than qualified to be riding this horse. And she totally understood the logic of the situation; but summoning up the courage to actually do it, was the challenge. And she did it!

It will take time for these two to learn to completely trust each other, but I am confident it will happen. Horses in general are happier when you let them move forward—especially a high energy horse. The key to good horsemanship is controlling the forward movement not trying to staunch it.

The underlying lesson for all of us is, that when our horses are acting emotional or resistant when we are riding, we must consider what WE are doing that is contributing to the problem. Often it is a “chicken and egg” scenario—is the rider afraid because the horse bucked or is the horse afraid because the rider contradicted herself by asking then snatching up the reins to stop? In the end it doesn’t matter which came first, because the dynamic is there now. But only one of you is capable of breaking the cycle.

You have to analyze and understand the problem, figure out the solution and then summon the courage to execute the solution. Breaking old dynamics is very hard but the outcome can be extremely rewarding, as it was in this case. We have several videos in the Horse Master with Julie Goodnight Academy site on this very subject. Hope you’ll check out the videos there and that you’ll join our Academy to watch: http://JulieGoodnight.com/search and enter key word “explosive canter.” You can watch this very horse and rider in the episode, “Let it Go,” when the new shows are posted there, too.

Enjoy the ride

—Julie Goodnight

-------------------------------------

Goodnight is proud to recommend Myler Bits, Nutramax Laboratories, Circle Y Saddles, Redmond Equine, Spalding Fly Predators, Troxel Helmets, Bucas Blankets and Millcreek Manure Spreaders. Goodnight is the spokesperson for the Certified Horsemanship Association.

Photo Credit: By Heidi Melocco, Whole-Picture.com